Born 1911 in Toledo, Ohio

Died October 23, 1964 in Stamford, Connecticut

Edward Eager is a most peculiar assortment of contradictions and surprises. His brief, decade-long span of writing children's books was almost a side line to his real calling, writing for the theater and yet it is for his children's books for which he is remembered. His writing style was inspired by Edith Nesbit and while in some ways he exceeds his idealized model, he never outshines her. The plots of his books center around perfectly ordinary children caught in extraordinary situations. His books remain among the favorites of 3rd-7th graders even fifty years after they were written and were well regarded on their initial publications but have never received any major awards.

Eager was born in 1911 in Toledo, Ohio where he lived for much of his childhood with a brief interlude in Australia and in later childhood a move to Maryland. Summers were spent in Indiana in the country. He attended Harvard University but became a critically successful playwright/lyricist while still a student with the production of his first play,

Pudding Full of Plums, in Cambridge. Inspired by this success, he left university without a degree to pursue the bright lights of Broadway and moved to New York City.

He married his childhood sweetheart, Jane Eberly, and they had a single son, Fritz. With a young child, and while continuing to be commercially successful writing plays, lyrics, screenplays for television and radio, etc., the Eager family moved to New Canaan, Connecticut where Eager was able to introduce his son to the wildlife and nature that he had himself so enjoyed as a child.

It was through reading to his son Fritz that Eager took it into his mind to write children's books. His first book,

Red Head, came out in 1951, and was a collection of poetry (Fritz was a red head). It was followed in 1952 by

Mouse Manor. Through his reading to Fritz, Eager came across the stories of E. Nesbit (Featured Author of

February 15, 2008) for the first time. He was inspired by her writing style and determined to create books of a similar ilk.

In 1954, he published

Half Magic, his first work in a series of four books that were to become loosely known as the

Half Magic series (the other titles in order of publication are

Knight's Castle,

Magic by the Lake, and

The Time Garden). It is not a traditional series in the sense of one book leading to another but more in the nature of C.S. Lewis's

The Chronicles of Narnia where characters or their children show up from one book to another but all encountering and trying to address the challenge of managing magic which always seems to yield something different from what was offered (the common theme with Nesbit). In addition to the four

Half Magic books, Eager wrote a further three fantasy book.

Magic or Not? and

The Well-Wishers go together and are stories in which it is never perfectly clear whether the protagonists are really dealing with magic or are instead simply experiencing improbable but not impossible coincidences.

Seven-Day Magic is a standalone magical fantasy novel unrelated to any of Eager's other works.

The quartet of children protagonists in

Half Magic are Jane, Mark, Katherine and Martha. The setting is the Toledo, Ohio of his Eager's own youth (circa 1920s). Daunted by the prospect of a long boring summer, the lives of the four siblings suddenly become remarkably lacking in boredom when they discover a magical talisman shaped like a coin. The drawback of this particular wonder is that it only grants half a wish with little to predict quite what half will be granted or what the consequences might be. One of the girls wishes that their cat could speak. With her wish, the cat does indeed become capable of speaking but only in a halfway feline pigeon English. The cat's attempts at communication become one of the many humorous interjections running throughout the story. As the cat describes them apropos something else, the children are "Idgwits! Foos!" when it comes to responsibly managing their magical gift. When Jane tries to undo the trouble, and being mindful that only half the wish will be granted, wishes that the cat will only in future be able to say Music, her good intentions are undone when the hapless cat, instead of being able to say mew, mew, mew, can only say sic, sic, sic.

Knight's Castle moves the adventures forward but through two sets of cousins, the two children of Martha and the two of Katherine.

Magic by the Lake returns to Jane, Mark, Katherine and Martha, while

The Time Garden revisits the cousins.

Across this series there are several things that stand out. One is just the plain antic humor sometimes verging on, but never quite falling over into, farce. It is a type of humor that seems to particularly appeal to children of this age and brings back a genuine smile of recognition from somewhat jaded adults. A second feature of the books is that they lend themselves to read-alouds at an age where a sea-change is happening. Children are able to read on their own but there is still an instinctive appeal of being read to. You want books with more substance than your typical read-alouds and the

Half Magic books fill the bill. Each chapter is a reasonably self-contained episode that makes for a natural reading session.

A third feature of Eager's writing is that he constantly and exuberantly plays with words. He has rich but not overdone prose descriptions. More importantly he always, as part of the humor, has a running set of word plays and puns going on. Again, it is something that is well pitched to children of this age who have mastered basic vocabulary and reading and are thrilled to find a writer who does not talk down to them but assumes that they will get the humor as they go along.

For children who are from a reading home, who have been read to extensively and are in turn bitten by the reading bug, there is yet a further pleasure in Eager's books. Not only does he not write down to children, he pays them the compliment of assuming they know more than they might actually know. He constantly pays tribute to reading in his books. The children always have books with them, books are not infrequently a key part of the plot and there are many allusions and references to other authors, stories and plots running throughout the narrative. The works of Edith Nesbit in particular make frequent appearances by one means or another. The result is that children with some framework of literary knowledge suddenly realize they are being invited in to that community of readers by an author who is assuming that they know something about that rich extra-corporeal world of literature; that they will get glancing allusions to

Little House on the Prairie, to the works of Sir Walter Scott and Lewis Carroll, to references to

Robinson Crusoe and

Little Women.

From a parent's perspective, these books are also wonderful for the image they put across of family dynamics. The children occasionally bicker and disagree with one another in a very familiar way. None-the-less, they look out for one another's best interests and respect one another in a very reassuring way. There is little that is dark or ambiguous or corrosive in these books. The children do things that are not always well planned out, are shocked by the consequences and then work to manage the consequences - all with good humor and a positive (though concerned) cast of mind.

Where to start? Definitely with

Half Magic. There are proponents for one or another of the subsequent books as being Eager's best but it all starts with

Half Magic.

Magic or Not? and

Well-Wishers are interesting books. They are separate from the

Half Magic series though they still are based on the actions and activities of a group of children. The chief difference (other than having a different cast of characters), is that it is never perfectly clear in either of the books whether there is actual magic going on or whether the events are just the consequence of possible but unlikely consequences.

The Time Garden has its apostles, but it is definitely for slightly older Independent Readers. There is a progression in reading maturity reflected in the transition from the four

Half Magic books to the ambiguous pair (

Magic or Not? and

Well Wishers) and finally to the stand-alone

Seven-Day Magic .

These are great books that can be enjoyed by young readers and adults alike. They are natural precursors of later fantasy writers for slightly older readers, writers such as Susan Cooper, Madeleine L'Engle and J.K. Rowling.

Enjoy these books and if your kids won't let you read the books to them, snag them and read for them your own pleasure.

Independent Reader

|

Half Magic by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker and Jack Gantos Highly Recommended

|

|

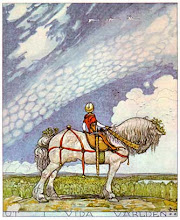

Knight's Castle by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker Highly Recommended

|

|

Magic by the Lake by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker Recommended

|

|

The Time Garden by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker Suggested

|

|

Magic or Not? by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker Recommended

|

|

The Well-Wishers by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker Suggested

|

|

Seven-day Magic by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker Suggested

|

Edward Eager BibliographyPudding Full of Plums written by Edward Eager (Play) 1943

Dream with Music written by Edward Eager (Play) 1944

The Liar written by Edward Eager (Play) 1950

Red Head written by Edward Eager and illustrated by Louis Slobodkin 1951

Mouse Manor written by Edward Eager and illustrated by Beryl Bailey-Jones 1952

The Gambler written by Edward Eager (Play) 1952

Half Magic written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1954

Jacques Offenbach, Orpheus in the Underworld written by Edward Eager (TV Adaptation) 1954

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, The Marriage of Figaro written by Edward Eager (TV Adaptation) 1954

Playing Possum written by Edward Eager and illustrated by Paul Galdone 1955

Knight's Castle written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1956

Adventures of Marco Polo: A Musical Fantasy written by Edward Eager (Play) 1956

Magic by the Lake written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1957

The Time Garden written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1958

Magic or Not? written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1959

The Well-Wishers written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1960

Seven-Day Magic written by Edward Eager and illustrated by N. M. Bodecker 1962

Call It Virtue written by Edward Eager (Play) 1963

Gentlemen, Be Seated written by Edward Eager (Play) 1963

Rugantino written by Edward Eager (Play) 1964

The Happy Hypocrite written by Edward Eager (Play) 1968